For the past seven years, a cyber-espionage group operating out of Russia—and apparently at the behest of the Russian government—has conducted a series of malware campaigns targeting governments, political think tanks, and other organizations. In a report issued today, researchers at F-Secure provided an in-depth look at an organization labelled by them as “the Dukes,” which has been active since at least 2008 and has evolved into a methodical developer of “zero-day” attacks, pulling together their own research with the published work of other security firms to provide a more detailed picture of the people behind a long-running family of malware.

Characterized by F-Secure researchers as a “well resourced, highly dedicated and organized cyberespionage group,” the Dukes have mixed wide-spanning, blatant “smash and grab” attacks on networks with more subtle, long-term intrusions that harvested massive amounts of data from their targets, which range from foreign governments to criminal organizations operating in the Russian Federation. “The Dukes primarily target Western governments and related organizations, such as government ministries and agencies, political think tanks and governmental subcontractors,” the F-Secure team wrote. “Their targets have also included the governments of members of the Commonwealth of Independent States; Asian, African, and Middle Eastern governments; organizations associated with Chechen terrorism; and Russian speakers engaged in the illicit trade of controlled substances and drugs.”

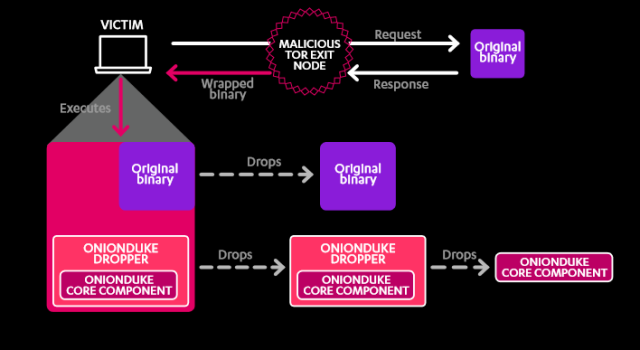

The first known targets of the Dukes’ earliest-detected malware, known as PinchDuke, were some of the first known targets and were associated with the Chechen separatist movement. By 2009 the Dukes were going after Western governments and organizations in search of information about the diplomatic activities of the United States and the North Atlantic Treaty Organization. While most of the attacks have used spear phishing e-mails as the means of injecting malware onto targeted systems, one of their attacks has spread malware through a malicious Tor exit node in Russia, targeting users of the anonymizing network with malware injections into their downloads.

The known components of the Duke malware family, in the order they have been detected by malware researchers at F-Secure, Kaspersky, Palo Alto Research, and others, are:

- PinchDuke: first detected in 2008, and last seen in 2010, this malware primarily targeted credentials for services such as Yahoo, Google Talk, and Mail.ru, as well as credentials stored in the Outlook and Mozilla Thunderbird e-mail clients and the Firefox browser. First seen used in conjunction with fake websites supporting Chechen insurgents, PinchDuke was also used to target government agencies in Georgia, Poland, the Czech Republic, Turkey, Uganda, and a US foreign policy think tank. The delivery vehicle was a malicious Microsoft Word or Adobe Acrobat file. PinchDuke was based on an openly available malware kit and was likely an opening experiment by the group in cyber espionage.

- GeminiDuke: designed to primarily collect configuration information about the targeted system, this malware appeared in January 2009 and was last detected active in December 2012. The malware reported back on user accounts, network settings, what software was running on the infected system, Windows environmental variables, and the names of files and folders in users’ home folders, My Documents. It also reported back recently accessed files, directories, and programs. The malware was likely used as a reconnaissance tool to target victims for further attack. It also had some code that attempted to stay persistent on the infected system.

- CosmicDuke: first spotted in January 2010, and still known to be active as recently as this summer, CosmicDuke is a more thorough information stealer, logging keystrokes and taking screenshots as well as stealing any data that gets copied to the Windows clipboard for pasting. It also searches for files with a specific extension to steal and grabs usernames, passwords, and any crypto keys it finds on the system. CosmicDuke also uses some persistence techniques that are based on the same approach used in GeminiDuke.

- MiniDuke: a multi-stage malware tool that uses a combination of loaders—some of which were used in conjunction with other malware in the family seen as early as July 2010. The main payload, first detected and analyzed in May 2011, was a backdoor that obtained its command and control server information via a Twitter account. The loader was seen active as recently as this spring; the backdoor hasn’t been seen since the summer of 2014.

- CozyDuke: also known as EuroAPT, CozyBear, CozyCar and Cozer, this modular malware implant can retrieve and run modules from a command and control server on demand, making it a bit of a chameleon. In addition to being a persistent backdoor, it has provided keylogging, screenshots, password stealing, and has stolen NT LAN Manager password hashes as well—possibly giving the malware the ability to spread laterally across local networks. “CozyDuke can also be instructed to download and execute other, independent executables,” F-Secure reported. “In some observed cases, these executables were self-extracting archive files containing common hacking tools, such as PSExec and Mimikatz, combined with script files that execute these tools. In other cases, CozyDuke has been observed downloading and executing tools from other toolsets used by the Dukes such as OnionDuke, SeaDuke, and HammerDuke.”

- OnionDuke: a backdoor first known to be active in February 2013 delivered by a dropper injected into Web downloads, OnionDuke got its name from the source of the injection—a malicious Tor exit node. Like CozyDuke, OnionDuke is modular, and has been used for a range of information stealing operations as well as to deliver distributed denial of service attacks and generate social media spam. It has also been distributed wrapped with legitimate software via Torrent files. OnionDuke was still active as recently as this spring.

- SeaDuke and HammerDuke: both of these recent backdoor malware appear to be installed as a secondary infection by CozyDuke. Its main purpose seems to be providing persistence and a backup backdoor in case the initial malware infection is detected. SeaDuke was first spotted in October 2014, and HammerDuke in January of this year.

- CloudDuke: a new downloader and malware loader, with two variants that also act as backdoors, CloudDuke was spotted first this June. While one variant uses a Web address controlled by the malware developers to get downloads, CloudDuke gets its name from its primary method of accessing files: a Microsoft OneDrive account.

A number of factors have led to the belief by researchers that the Dukes group is based in Russia and at least tangentially associated with the Russian government. First, the targets have been aligned with Russian government interests. There are also a number of Russian-language artifacts in some of the malware, including an error message in PinchDuke: “Ошибка названия модуля! Название секции данных должно быть 4 байта!” (which translates essentially as “Error in the name of the module! Title data section must be at least 4 bytes!”). GeminiDuke also used timestamps that were adjusted to match Moscow Standard time.

There is also the timing of some of the attacks that suggests at least a Russian state sponsor was behind the group. In 2013, before the beginning of the Ukraine crisis, the group began using a number of decoy documents in spear phishing attacks that were related to Ukraine, including "a letter undersigned by the First Deputy Minister for Foreign Affairs of Ukraine, a letter from the embassy of the Netherlands in Ukraine to the Ukrainian Ministry of Foreign affairs, and a document titled 'Ukraine’s Search for a Regional Foreign Policy,'" the researchers noted. "It is...important to note that, contrary to what might be assumed, we have actually observed a drop instead of an increase in Ukraine-related campaigns from the Dukes following the country’s political crisis." That would indicate that the campaign was part of an intelligence-gathering effort leading up to the crisis.

“Based on our establishment of the group’s primary mission,” F-Secure’s researchers wrote, “we believe the main benefactor (or benefactors) of their work is a government. But are the Dukes a team or a department inside a government agency? An external contractor? A criminal gang selling to the highest bidder? A group of tech-savvy patriots? We don’t know.” Whoever it might be, based on how long the group has been operating, it would seem that the Dukes have substantial, reliable financial support. And because their campaigns appear to have been well-coordinated over time, with no apparent cases of overlap between attacks or interference between malware, the F-Secure team concluded, “We therefore believe the Dukes to be a single, large, well-coordinated organization with clear separation of responsibilities and targets.”

Such an organization operating in Russia would most likely require state acknowledgement, if not outright support.

reader comments

28