Macs older than a year are vulnerable to exploits that remotely overwrite the firmware that boots up the machine, a feat that allows attackers to control vulnerable devices from the very first instruction.

The attack, according to a blog post published Friday by well-known OS X security researcher Pedro Vilaca, affects Macs shipped prior to the middle of 2014 that are allowed to go into sleep mode. He found a way to reflash a Mac's BIOS using functionality contained in userland, which is the part of an operating system where installed applications and drivers are executed. By exploiting vulnerabilities such as those regularly found in Safari and other Web browsers, attackers can install malicious firmware that survives hard drive reformatting and reinstallation of the operating system.

The attack is more serious than the Thunderstrike proof-of-concept exploit that came to light late last year. While both exploits give attackers the same persistent and low-level control of a Mac, the new attack doesn't require even brief physical access as Thunderstrike did. That means attackers half-way around the world may remotely exploit it."BIOS should not be updated from userland and they have certain protections that try to mitigate against this," Vilaca wrote in an e-mail to Ars. "If BIOS are writable from userland then a rootkit can be installed into the BIOS. BIOS rootkits are more powerful than normal rootkits because they work at a lower level and can survive any machine reinstall and also BIOS updates."

You will go into a deep sleep

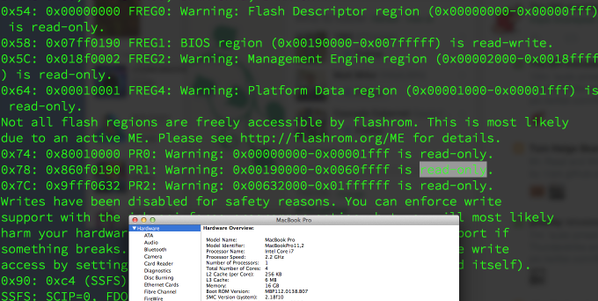

Vilaca's exploit works by attacking the BIOS protections immediately after a Mac restarts from sleep mode. Normally, the protection—known as FLOCKDN—allows userland apps read-only access to the BIOS region. For reasons that aren't clear to the researcher, that FLOCKDN protection is deactivated after a Mac wakes from sleep mode. That leaves the firmware open to apps that rewrite the BIOS, a process typically known as reflashing. From there, attackers can modify the machine's extensible firmware interface (EFI), the firmware responsible for starting a Mac's system management mode and enabling other low-level functions before loading the OS.

"The flash is unlocked and now you can use flashrom to update its contents from userland, including EFI binaries," Friday's blog post stated, referring to the freely available utility for reading, writing, erasing, and verifying firmware contained in flash chips. "It means Thunderstrike like rootkit strictly from userland."

To work, an exploit would require a vulnerability that provides the attacker with unfettered "root" access to OS X resources. Such vulnerabilities aren't always easy to find, but they're by no means impossible, as demonstrated by the Rootpipe privilege escalation bug that came to light late last year. Vilaca said a drive-by exploit planted on a hacked or malicious website could be used to trigger the BIOS attack.

"The bug can be used with a Safari or other remote vector to install an EFI rootkit without physical access," Vilaca wrote. "The only requirement is that a suspended happened [sic] in the current session. I haven’t researched but you could probably force the suspend and trigger this, all remotely. That’s pretty epic ownage ;-)."

An attacker could add code that deliberately sends a targeted Mac into sleep, or the exploit could be programmed to detonate the BIOS payload the next time a machine comes out of sleep mode. In either case, once the Mac awakes it would be possible for the attacker to bypass OS X firmware protections and rewrite the BIOS.

"An exploit could either verify if the computer already went previously into sleep mode and it's exploitable, it could wait until the computer goes to sleep, or it can force the sleep itself and wait for user intervention to resume the session," Vilaca told Ars. "I'm not sure most users would suspect anything fishy is going on if their computer just goes to sleep. That is the default setting anyway on OS X."

As was the case with Thunderstrike, Vilaca said he doesn't think his attack is likely to be exploited on a mass scale. Instead, it would likely be exploited only in highly targeted attacks, say those carried out against high-value targets the attackers know and have a high interest in.

Vilaca said he has confirmed his attack works against a MacBook Pro Retina, a MacBook Pro 8.2 and a MacBook Air, all of which ran the latest available EFI firmware from Apple. He said Macs released since mid to late 2014 appear to be immune to the attacks. He said he wasn't sure if Apple silently patched the vulnerability on newer machines or if it was fixed accidentally. Ars has asked Apple for comment, but company officials generally don't discuss security issues until a fix has been released.

At the moment, Vilaca said, there isn't much users of vulnerable machines can do to prevent exploits other than to change default OS X settings that put machines to sleep when not in use. More advanced users can download software made available by Trammell Hudson, creator of the Thunderstrike exploit. Available here and here, Hudson's software dumps the contents of a Mac's BIOS chip so users can compare the results against firmware files provided by Apple. This safeguard doesn't prevent users from having their Mac firmware rewritten, but it will alert them if such an attack has occurred.

"I asked Apple to start publishing these files and their signatures so we can have a good baseline to compare against," Vilaca wrote in his blog post. "Hopefully they will do this one day. I built some tools for this purpose but they aren't public."

While the attack isn't likely to be exploited on a mass scale, it's also not hard for people with above-average skill to carry it out. The technique joins a growing roster of attacks that rewrite firmware with a malicious replacement. Besides Thunderstrike, such exploits include BadUSB and attacks against VoIP phones, home and small office routers, and hacks tied to the National Security Agency that hid inside the firmware of hard disk drives. Given the inability of most current security products to detect malicious firmware, such attacks could one day represent a significant threat unless manufacturers devise ways to ensure the authenticity of the firmware powering the devices they sell."We need to think different and start a trust chain from hardware to software," Vilaca wrote. "Everyone is trying to solve problems starting from software when the hardware is built on top of weak foundations. Apple has a great opportunity here because they control their full supply chain and their own designs. I hope they finally see the light and take over this great opportunity."

Headline updated to remove the word "remote" since the hack involves use of a local exploit.

reader comments

103